What’s it Worth to You? Measuring the Economic Value of Natural Areas

By Michael Reinemer, Editor

As buildings, developments and populations grow, Mother Nature is feeling the pinch. Or punch. Clean water is more scarce. Prairie and parklands get paved over. Our remaining wild places are often squeezed into small, fragile fragments.

Nature could use a good economist or a business manager right now.

When proposals emerge that list the economic benefits of developing, draining or mining a natural area, or building a data center, how do we factor in the dollar cost of environmental damage? And the economic benefits derived from leaving the place alone?

For decades, conservationists, business leaders and economists have been working on ways to answer those questions.

Seeing the forest, not just the trees

Historically, we put price tags on the current value of the chunks extracted from nature measured in units like board-feet of timber or tons of coal. And these chunks are taken from natural resources that we once believed were not only free but inexhaustible. Until recent decades, we haven’t really assessed the values of nature at scale—treating nature as large, integrated ecosystems that provide value now and far into future.

The idea of “natural capital” gained traction beginning in the 1990s when one study estimated the annual value of the world’s ecosystems at $33 trillion in economic benefits to humans. That’s approximately the same value as the gross world product at that time (the combined value of all countries’ gross domestic product).

In his 2005 book “Investing in Nature,” entrepreneur-turned-conservationist William Ginn, argued that in order to conserve nature at scale, people need to leverage market forces, which also operate on a large, global scale. “Markets and market-based conservation tools are powerful complements to old-fashioned land conservation.”

Not that there’s anything wrong with old-fashioned conservation. But, says Ginn, “commerce is a formidable force with no inherent environmental conscience driving it. Only we can shape its direction. Understanding the nature of business may be the best tool we have to put nature in business.”

Ginn describes several strategies with examples from across the U.S. and the world: conservation investment banking, which uses capital to achieve conservation goals while meeting business needs; new environmental markets like “grassbanks” that allow ranchers to graze livestock while preserving wildlife habitat; and incentive programs to move companies toward sustainable, green products.

Measuring natural values in land use decisions

Valuing natural areas should apply to everyday, local decisions about land and water use. Matthew Winden, an economics professor at University of Wisconsin-Whitewater, discussed this during the League’s national convention in July.

Winden says developers have an advantage when they propose a development project that would displace a natural area. That’s because the expected benefits, like jobs and tax revenue, are easy to understand and quantify—and policymakers understand those categories.

The benefits of conserving a natural area can also be measured—as ecosystem services. Forests, wetlands and meadows serve as filters for clean water. Clean waterways offer opportunities for spending on outdoor recreation—boating, fishing, swimming. Natural areas sequester carbon, reducing the impact of climate change. Trees help clean air and reduce the heat in urban areas.

Yet these benefits often get under reported, Winden says. However, we can assign what’s known as direct-use value to these ecosystem services. A wetland, for example, offers at least two important, tangible benefits— filtration for clean water and absorbing storm water to control flooding.

Other natural benefits may be harder measure and harder for the public to grasp. Like the “intrinsic value that such a place exists,” or existence value. The Arctic National Wildlife Refuge is perched on the northeastern coast of Alaska. It’s very difficult and expensive to visit. Yet, many Americans value the fact that the refuge exists as a completely wild, untrammeled sanctuary. It’s an immensely important destination for breeding birds from every corner of the world and home to polar bears, wolves, caribou and other wild creatures.

Likewise, parkland with trees or bike paths increases the value of nearby homes and boosts their tax rate, which provides economic benefits to the community.

Then there are non-use values. That means preserving the option to use them in the future, including their value to future generations, which is known as a bequest value.

Still it’s important to speak the language of economics, Winden says. “Converse in the language of dollars and cents.” Using these methods allows proponents of natural areas to compete with values assigned to other uses, like development, mining or timber harvests.

With University of Wisconsin colleagues Russ Kashian and Emmer Shorts, Winden examined the case where Muskego, Wisconsin, restored an abandoned railroad corridor as a bike path in 2000. Their analysis published in Journal of Park and Recreation Administration, found the bike path had a positive, statistically significant impact on property values. The restoration increased values by 8.6 percent for homes directly adjacent to the path. Economists call this hedonic pricing.

Water clarity also affects home values and tax revenues. Healthy lakes can provide clear, measurable benefit to the local economy. Looking at the reverse, an economist could also estimate the cost or decrease in value tied to an algal bloom, caused by excess nutrients or other pollutants that make a lake toxic or unpleasant to visit.

The bottom line for conservationists? We need to make environmental valuations a standard step in land use decisions. Embed them in the planning, awareness and policy process. Give decision makers real data that reflects the real value of natural areas. “Make it impossible to ignore,” Winden says.

Trading shares of natural areas

What if there were a standard way to measure the economic value of a natural area so we could invest in it and profit from the benefits it delivers or its appreciation over time?

Recently the New York Stock Exchange approved the concept of allowing the public to trade “natural asset companies (NAC).” NACs would represent the value of a parcel of land leased to the company that would issue shares investors could buy and trade like stocks on an exchange, such as the New York Stock Exchange or NASDAQ.

The idea is to define the economic value of natural areas and invest in them. One example would apply to working lands. Imagine a struggling farmer who grants a long-term lease to a NAC, which licenses the rights to benefits from the farm produces. Shares in the NAC would be traded publicly, attracting investors who recognize the value of the land.

The farmer or landowner would receive income from the sale of shares and that revenue could be invested in improving the land. This could help bring regenerative agriculture to scale, creating more sustainable farming with better nutrient management and less water pollution.

Unfortunately, an anti-conservation group called American Stewards of Liberty mobilized several states and members of Congress to oppose the idea, painting it as a “radical climate agenda” and dissuaded the Securities and Exchange Commission from permitting trading of NACs.

But the idea is not dead. In May, the Gabelli School of Business at Fordham University announced an agreement with the Intrinsic Exchange Group, the company that pioneered the idea of natural asset companies. Barbara Porco, associate dean at the business school, says their Responsible Business Center will oversee creation of an independent accounting framework for “ecological performance reporting,” which she calls “an important step in the development of and marketplace acceptance for natural capital as an asset class.”

By creating Intrinsic Exchange Group in 2017, CEO Douglas Eger established one way to leap frog the slow policymaking process and take the environment investments directly to the market. He views NACs as one way to get past what he calls the false dichotomy of “nature vs. economic development.”

Putting a price tag on pollution

GDP, gross domestic product, is a well-known measure of a country’s economic output or revenue. But missing from that calculation is the environmental cost. In terms of dollars, what is the cost of land degradation and water and air pollution connected to GDP? Some economists have been working for many years on a new metric, gross external damages (GED). That has garnered some attention from the federal government. In 2023, the White House issued a report on a national strategy “to put nature on the nation’s balance sheet.”

Daniel Phaneuf, a professor in the Agricultural and Applied Economics department at the University of Wisconsin, focuses on understanding the economic costs of water pollution in the U.S. and was among the first to measure GED connected to water pollution.

A July 2025 paper, “Gross External Damages of Water Pollution in the United States,” is one of the first to estimate GED for water pollution. Phaneuf, David Keiser from University of Massachusetts- Amherst and other researchers examined five areas in which water pollution has a harmful economic impact: water-based recreation, property values, drinking water treatment, human health and climate change. And they created a model to estimate the costs of damage in those areas.

The researchers looked at the GED or economic damage from excess nutrients (such as nitrate and phosphorus) and the model found nutrient pollution in our waterways costs between $40 billion and $100 billion per year.

They note that agriculture contributes the largest share of water pollution and more than one third of GED, but municipal wastewater accounts for the largest share of economic damages—an argument for better pollution abatement measure at water treatment facilities. Costs are higher near population centers and water treatment plants, and a significant proportion of the pollution flows to downstream communities.

Our lingering bias toward extraction

Meanwhile, looking at the natural world broadly, it’s safe to say bias toward extraction is alive and well-funded. The volume of greenhouse gas emissions is expected to break a record this year. Plastic pollution costs us as much as $1 trillion per year. And while the concept of “balance of nature” is out of date, we should definitely consider “balance sheet nature,” integrating natural capital into economics and corporate balance sheets.

Cover story from Outdoor America, Issue 4, 2025

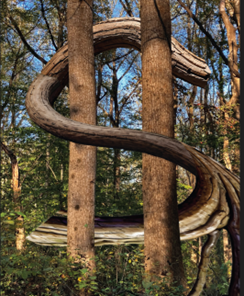

Photo illustration by Leif Siegrist, photos Michael Reinemer

Your kit will include a bottle containing 25 nitrate test strips which you can use to test your water source(s) throughout the year. You’ll also receive postcards explaining how to use your nitrate test strips and how to share your Nitrate Watch results on the Clean Water Hub.

Your kit will include a bottle containing 25 nitrate test strips which you can use to test your water source(s) throughout the year. You’ll also receive postcards explaining how to use your nitrate test strips and how to share your Nitrate Watch results on the Clean Water Hub. Your kit will include four test strips so you can test your waterway throughout the season. You’ll also receive a chart to help you interpret your results and a postcard with instructions for completing a Salt Watch test and reporting your findings.

Your kit will include four test strips so you can test your waterway throughout the season. You’ll also receive a chart to help you interpret your results and a postcard with instructions for completing a Salt Watch test and reporting your findings.