As Impacts of Nitrate Pollution Loom Large, Volunteers Step Up

By: Heather Wilson, Save Our Streams Coordinator

Across much of the United States, nitrate is perhaps the most widespread and dangerous contaminant in our waterways. This colorless, odorless, tasteless compound is an essential nutrient for plant growth, applied to the landscape in chemical fertilizers and manure. But this nutrient becomes a harmful pollutant when it reaches the water.

In streams and lakes, nitrate pollution causes an ecological imbalance that is responsible for producing algae blooms and areas devoid of oxygen, called dead zones. When a waterway receives a large influx of nitrate pollution, fish and other aquatic life can suffer a sudden die-off event, otherwise known as a fish kill.

In our drinking water, elevated nitrate poses a serious threat to human health contributing to increased incidence of thyroid disease, pre-term births, neural tube birth defects and bladder, ovarian and colon cancers.

Unfortunately, none of this is news. We’ve long understood the sources and impacts of nitrate pollution, and yet it persists. The most effective solutions are well known, but their use is far too limited.

This issue was on full display in Iowa this year as water utilities publicly struggled to protect residents from the harmful impacts of nitrate pollution. In a state with the nation’s second-highest rate of cancer incidence (and one of only two states whose cancer rate is increasing), the stakes could not be higher.

A bad year for Iowa

The largest sources of nitrogen pollution in the United States are tied to agriculture, mainly chemical fertilizer and manure from farm fields and animal feeding operations. Iowa, with an estimated 84 percent of its land devoted to agricultural production, has long contended with this issue.

In the summer of 2025, Iowa’s struggle with nitrate pollution reached a new level when Central Iowa Water Works, the water supplier for over 600,000 Iowans, imposed a ban on lawn watering. The reason? High nitrate in the Des Moines and Raccoon Rivers.

These rivers, which serve as source water for Central Iowa Water Works, had nitrate concentrations far in excess of 10 mg/L (milligrams per liter), which is the maximum level allowed in drinking water under the federal Safe Drinking Water Act. Frequently this summer, both rivers had nitrate concentrations exceeding 15 mg/L.

(Peer-reviewed studies suggest that prolonged exposure to nitrate in drinking water—even below the accepted 10 mg/L standard—poses threats to our health. The Izaak Walton League has pushed for a review of that guideline.)

Even with Water Works’ state-of-the-art nitrate removal facility operating at full capacity, it was difficult to keep nitrate concentrations in finished drinking water below the 10 mg/L standard. To ensure that they could deliver drinking water to customers that did not exceed the regulatory nitrate standard, the water utility had to reduce demand for water by issuing a ban on all lawn watering. In other words, the utility needed to reduce other uses of water to dilute nitrate pollution.

This first-of-its kind ban lasted from June 12 to July 31, a total of 49 days. The nitrate removal facility operated for over 110 days in 2025. This facility is reported to cost up to $16,000 daily when it is in operation. This cost is ultimately passed on to customers.

Pinpointing the source

The lawn watering ban in central Iowa shone a spotlight on water quality issues in the region and presumably caused many Iowans to wonder “where is this nitrate pollution coming from?” Coincidentally, a scientific report that answered that question would be released on July 1, right in the middle of the lawn watering ban.

The Central Iowa Source Water Research Assessment, or CISWRA, is an unbiased, scientific study commissioned by the Polk County Board of Supervisors. (Polk County is Iowa’s most populous county, including Des Moines and much of the Greater Des Moines metropolitan area.) The CISWRA report, which was roughly two years in the making, takes a detailed look at what contaminants are present in Polk County’s watersheds and the sources of those contaminants. Some key takeaways from the report include:

On average, more than three fish kills occur in the Raccoon and Des Moines watersheds each year. Since 1996, fish kills in these watersheds have led to a loss of more than $732,000. This sum only accounts for the direct replacement value of the fish and doesn’t include indirect costs associated with losses in recreation, business and ecosystem services.

- Over 75 percent of nitrogen and phosphorus pollution in the Raccoon and Des Moines Rivers comes from agricultural sources.

- 54,000 tons of nitrogen flow past the city of Des Moines every year, equivalent to about 70 1,000-plus gallon cargo tanks each day. That’s roughly $43 million in wasted fertilizer lost to the environment.

- Over the past two decades, nitrate in the Raccoon and Des Moines Rivers has exceeded 10 mg/L about 15 percent of the time, requiring Des Moines Water Works to treat the water at great expense.

- On average, more than three fish kills occur in the Raccoon and Des Moines watersheds each year. Since 1996, fish kills in these watersheds have led to a loss of more than $732,000. This sum only accounts for the direct replacement value of the fish and doesn’t include indirect costs associated with losses in recreation, business and ecosystem services.

Not only did this report answer important questions about sources of pollution in central Iowa, it also drew increased attention to water quality issues from concerned citizens across the state. While the report was focused on Polk County, its findings and mitigation advice were relevant to watersheds statewide. At an August 4 presentation of findings from the CISWRA report, nearly 900 attendees joined in person and online to hear directly from a panel of scientists involved in the creation of the report.

We know the solutions

How do we keep nitrate pollution out of our water in the first place? The good news is that numerous well-researched solutions exist. In short, we need to keep nitrogen in the field where it belongs and reduce excess use.

Many of the best practices to mitigate nutrient pollution focus first on the soil. Conventional agricultural practices strip soil of its organic material and decrease its ability to retain water. When it rains, water moves quickly off the field—taking nutrients with it and causing erosion—instead of infiltrating through the soil as it should. Unhealthy soils also necessitate higher use of fertilizers, adding to the problem.

Regenerative agricultural practices work to restore the soil’s organic matter, increase porosity and reduce a farm’s reliance on inputs (such as chemical fertilizer or pesticides). A cover crop, for example, can be grown in the off-season to provide a shield for the soil and keep it in place. Over time, it will also help increase the soil’s organic matter and ability to take in water.

Other tools in the toolbox protect and replicate natural processes to filter out nitrate. In Iowa, less than two percent of the state’s original wetlands remain. Protecting and restoring them is one of the best strategies available to address nitrate pollution. Installing practices on the edge of a field, like bioreactors and saturated buffers, can also play a role by treating water before it reaches a local stream or waterway.

Barriers to progress

The solutions are known. The public is fed up. So why are waterways still receiving so much nitrate pollution?

It turns out that there are several factors preventing needed water quality progress in Iowa and other regions across the U.S.

Conservation programs are underfunded and oversubscribed. Installing conservation practices requires an investment in knowledge, equipment and supplies. To encourage farmers and landowners to install conservation practices on their land, the U.S. relies on a system that provides incentives and support for participating farmers. These incentives are delivered via federal programs at the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Natural Resources Conservation Service (USDA-NRCS), including the Conservation Stewardship Program, Environmental Quality Incentives Program and Conservation Reserve Program.

These programs offer the largest single source of funds to help farmers and ranchers understand and adopt critically important conservation practices on the landscape. Yet, the programs are underfunded and oversubscribed. In recent years, only about one-third of applicants seeking help putting conservation on the ground through working lands programs receive it; the rest are turned away for lack of funding. In 2023, only 27 percent of Iowa applications were funded.

Reductions in the Department’s workforce have exacerbated this problem. While some USDA employees are based in Washington, 99 percent of NRCS staff are local, helping the farmers in their communities with technical assistance related to conservation. Yet, since January of this year, more than one in four of these important staff have been lost. This raises serious concerns about NRCS’ ability to assist with conservation projects across the country.

State-sponsored water monitoring takes another hit. Despite continued assertions that nutrient reduction in waterways is a goal for the state, water monitoring in Iowa continues to suffer setbacks. The most recent setback—the Iowa Legislature cut funding for a network of in-stream water monitoring sensors that measure nitrate, among other contaminants. This network includes sensors deployed by the University of Iowa (UI), the USDA and the U.S. Geological Survey. With the loss of funding, the number of UI sensors will drop from 60 to 0 in the summer of 2026.

For roughly 10 years, this network of nitrate sensors, part of the Iowa Water Quality Information System, has provided real-time data about nitrate pollution in Iowa’s waterways, helping researchers and the public learn more about how nitrate moves through a watershed and how various methods might work to mitigate the runoff.

Despite the value of this sensor network, the Iowa Legislature decided to eliminate funding for the UI sensors, shrinking the total sensor network by approximately two thirds. This hinders our collective ability to track progress or detect nitrate pollution. It also reduces the amount of information available to water utilities that need to quickly respond to an influx of nitrate in source water. The League’s Iowa Division has started a crowdfunding campaign to raise the funding for these sensors.

EPA steps in to remove stream segments from Iowa’s impaired waters list. Under the Clean Water Act, states are required to identify waters that are not suitable for their designated uses, such as swimming, fishing or supporting aquatic life, due to pollution. Once listed, states develop specific pollution reduction strategies focused on contaminants, such as nitrate, identified by the state. In August, the EPA took the uncharacteristic action of rescinding its previous decision to add seven stream segments to Iowa’s impaired waters list. These segments, including parts of the Des Moines, Raccoon, Cedar, Iowa and South Skunk Rivers, are known to have nitrate levels that frequently exceed the drinking water threshold of 10 mg/L.

In November 2024, the EPA determined that these seven stream segments needed to be on Iowa’s impaired waters list because they exceeded safe drinking water standards. The events of this summer support this decision. After all, the lawn watering ban put in place by Central Iowa Water Works was a direct result of soaring nitrate levels in the Des Moines and Raccoon Rivers. Nevertheless, these segments were once again removed from Iowa’s impaired waters list, leaving them more vulnerable to further pollution.

Iowa is committed to its Nutrient Reduction Strategy, despite a lack of results. Since 2013, the Iowa Nutrient Reduction Strategy (NRS) has been a part of virtually every conversation about nutrient pollution in Iowa. Iowa adopted the NRS to satisfy a policy from the EPA urging states to address nutrient pollution. The NRS requires certain action from point-source polluters, such as wastewater treatment plants and industrial operations. Agriculture, considered a non-point source of pollution, is only subject to voluntary measures. This means that farmers are under no obligation to adopt practices that will prevent pollution from their operation from entering nearby waterways or groundwater.

This voluntary approach has led to little measurable progress toward nutrient reduction goals. The stated goal of the NRS is to reduce annual nitrogen and phosphorus loss by 45 percent. The water quality data shared on NRS dashboards hosted by Iowa State University illustrate that progress toward this goal has been minimal, at best. In fact, the amount of nitrogen leaving the state has slightly increased since the adoption of the NRS.

Despite the lack of results, politicians and leaders embrace the NRS. They point to the number of conservation practices installed and the amount of money spent on the initiative as signs of success. Notably, they do not measure success based on documented improvement in water quality or actual reduction of nutrients running off the land.

Consider the “signs of success.” A 2022 Iowa Environmental Council analysis noted that at the current rate of adoption of conservation practices, Iowa will meet its NRS goals for cover crops in 85 years, it will meet its goals for wetland conservation in 942 years, and it will take 22,325 years to reach the NRS goals for bioreactors and saturated buffers.

And when the amount of nitrogen Iowa sends to the Gulf of Mexico is increasing instead of declining, it is hard to understand how the Nutrient Reduction Strategy’s implementation could be considered a success.

Nitrate Watch volunteers step up

In the face of a nitrate pollution crisis, concerned citizens increasingly turned to the Izaak Walton Leauge’s Nitrate Watch program as a hands-on, meaningful way to do something about nitrate pollution.

The Izaak Walton League has fulfilled record-breaking numbers of kit requests from volunteers, especially Iowans. In August alone, we had requests for more than 500 kits. The uptick was spurred by extensive media coverage of the nitrate threat, including the central Iowa lawn watering ban, the CISWRA Report and the growing popularity of the Nitrate Watch program.

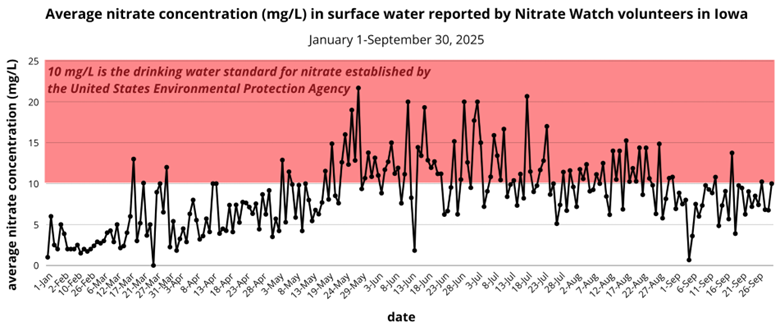

This massive influx in kit requests has also meant a marked increase in data reporting. At the time of writing (October 2025), Nitrate Watch volunteers have submitted 3,428 nitrate readings in 2025. These readings, reported at 1,364 sites in 35 states and the District of Columbia, report nitrate concentrations in surface water (including rivers, lakes, streams) as well as drinking water. This already exceeds last year’s total of 2,469 Nitrate Watch readings submitted at 939 sites.

And volunteers are documenting dangerous levels of nitrate in surface waters. This year, 29 percent of surface water test results report nitrate levels greater than or equal to 10 mg/L, the Safe Drinking Water Act maximum threshold for nitrate in public drinking water. (Most of these results—56 percent—were reported by volunteers in Iowa.)

The impact of community science

A strong uptick in volunteer water quality monitoring is a hopeful sign. Of course, increased monitoring means more data that can be used to understand the scope and scale of nitrate pollution at a local and regional level. The data is also important in increasing each volunteer’s individual understanding of the nitrate pollution problem in the waterways that they care about and rely on.

Water monitoring also presents a jumping-off point for volunteers interested in deepening their involvement. With support from Izaak Walton League staff, several Nitrate Watch volunteers have taken a step beyond data reporting by sharing their data and their testimonial with lawmakers. Other volunteers have shared their monitoring stories in news media, blog posts or on social media.

Whether they are reporting results, talking to neighbors, contacting lawmakers, posting about their findings or all of the above, Nitrate Watch volunteers are making a difference. Their efforts continue to shine a light on a pollution problem with serious impacts on public health and environmental quality, and provide tangible evidence that people are not willing to ignore this threat. We are excited to see the growing energy from our volunteers and partner organizations, and we look forward to continuing to work together to press for solutions.

Nitrate is a National Problem

This article uses Iowa’s nitrate crisis as a case study, but nitrate pollution is causing issues in waterways nationwide—and worldwide, for that matter.

Other midwestern states, like Minnesota and Wisconsin, are facing similar challenges to Iowa. The “Nitrates on Tap” report, released in September 2025 by the Alliance for the Great Lakes and Clean Wisconsin, outlines the scope and impacts of Wisconsin’s own nitrate crisis.

States far from the Midwest are also grappling with nitrate pollution. In eastern Oregon and California’s central valley, nitrate pollution in groundwater poses a serious public health risk for well users. In lakes across the country, from Lake Erie to Lake Okeechobee, algae blooms fed by nitrate and phosphorus pose challenges for recreation, safety and environmental quality every summer.

The sources and impacts of nitrate pollution are varied, and they impact communities across the country. After all, we’re all downstream from someone.

Partner Organizations Step Up Too

Volunteers working alone can create an incredible impact, but local and regional organizations can help amplify the work of individuals united by a shared vision. Nitrate Watch partner organizations serve a vital role by providing local expertise and support to volunteers. Here are just a few examples of Nitrate Watch partner organizations stepping up to raise awareness and support volunteers in 2025:

The newly formed Nishnabotna Water Defenders, a grassroots advocacy group in southwest Iowa, has embraced Nitrate Watch as a way for community members to understand the presence and impacts of nitrate pollution locally. They launched a series of billboards in the fall of 2025 urging Iowans to “Know What You drink” and “Monitor Nitrate in Your Water.”

Carver County Water Management Organization in Carver County Minnesota launched a direct mail campaign in July that provided information about nitrate pollution to residents in the Bevens and Silver Creek watersheds, which are known to have high nitrate levels. In their communication, they directed residents to the Nitrate Watch program, resulting in more than 50 kit requests from residents.

Wisconsin’s Green Fire is a new Nitrate Watch partner with big plans. Their organization has launched a Nitrate Watch page on their website including educational resources and a co-branded Nitrate Watch kit request form. In just a few months, volunteers with the group have already reported data at more than 25 sites across Wisconsin.

Over the past two years, Iowa Citizens for Community Improvement (Iowa CCI) has built a large and active network of volunteer water monitors across Iowa, reporting over 900 readings at more than 200 sites in 2025. Iowa CCI supports their volunteers by hosting monthly Zoom calls in the summer to hear from guest speakers, share ideas, answer questions and discuss current water quality issues and opportunities for advocacy.

Story from Outdoor America, Issue 4, 2025

Your kit will include a bottle containing 25 nitrate test strips which you can use to test your water source(s) throughout the year. You’ll also receive postcards explaining how to use your nitrate test strips and how to share your Nitrate Watch results on the Clean Water Hub.

Your kit will include a bottle containing 25 nitrate test strips which you can use to test your water source(s) throughout the year. You’ll also receive postcards explaining how to use your nitrate test strips and how to share your Nitrate Watch results on the Clean Water Hub. Your kit will include four test strips so you can test your waterway throughout the season. You’ll also receive a chart to help you interpret your results and a postcard with instructions for completing a Salt Watch test and reporting your findings.

Your kit will include four test strips so you can test your waterway throughout the season. You’ll also receive a chart to help you interpret your results and a postcard with instructions for completing a Salt Watch test and reporting your findings.