The glass is half empty.

Once, clean fresh water was something we could take for granted. That’s no longer possible. Clean water, essential to our survival and a basic human right, is increasingly scarce. About one half of one percent of the water on Earth is clean

and readily available.

At our current rate of consumption, the world may run out of water by 2040, says a 2023 report from the Bank of America Global Research. A March 2024 report from the University of Miami predicts severe shortages in the decades ahead in the U.S. We’re

accustomed to hearing about the dire shortages and water wars in the arid regions of the West, but they are now appearing in Eastern regions as well.

The good news: we have water conservation technologies, policies and practices that could preserve supplies of clean water for generations to come—if we apply them broadly across industries and our individual households.

At what cost?

Keeping water clean and plentiful comes at a cost.

What we directly pay for water varies depending on where we live. It’s not just the monthly bill from our water utility. The cost of clean water also shows up in what we pay in taxes for infrastructure, for food, energy, healthcare—and even

computing power.

In some cases, what we pay may appear to be artificially low due to how it is priced, regulated and dispersed over many parts of our economy. Water prices “typically lag behind demand,” notes Haim Israel, Head of Global Thematic Research for

Bank of America.

So it’s worth taking a look at how access to fresh water will be affected by consumption trends, climate, contamination and conservation.

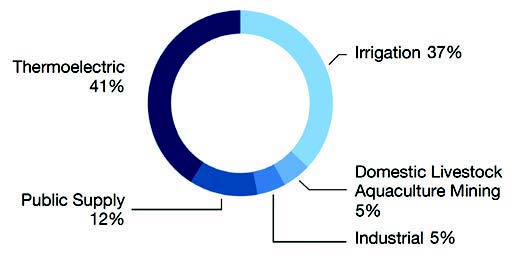

Water use by category for 2015, the most recent data available from U.S. Geological Survey.

Water use by category for 2015, the most recent data available from U.S. Geological Survey.Consumption

According to the most recent (2015) data from the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS), Americans use about 322 billion gallons of water per day in the U.S., and 87 percent of that is fresh water.

Agriculture consumes a vast amount of both ground and surface water in the United States. Irrigation accounts for 42 percent of the nation’s total fresh water withdrawals. Globally, water for agricultural irrigation accounts for 72 percent of withdrawals

of fresh water.

Aquifers that supply 90 percent of water systems in the U.S. and irrigate “some of the world’s most bountiful farmland” are now dwindling, threatening the ability to support industrial-scale agriculture, according to a series published

in the New York Times in 2023. The newspaper quoted Don Cline, USGS associate director for water resources, who said there is no way to replenish that lost groundwater—or even explain what it means to the public. “There’s

almost no way to convey how important it is.”

Thermoelectric power—creating steam by burning coal or oil, for instance—accounts for at least 133 billion gallons per day, representing 34 percent of total freshwater use in the U.S.

Data centers represent a relatively new but major source of water use. Huge arrays of large servers consume a vast and growing amount of electricity. The computers generate a lot of heat that requires water for cooling. Today, data centers

are among the 10 largest consumers of water.

One large data center can consume as much as five million gallons per day—roughly as much as a town of 50,000 would consume daily. These data centers now appear in many parts of the U.S., including Iowa, where Microsoft has data centers that use

a supercomputer designed to train its artificial intelligence (AI) models.

Kerri Johannsen, energy program director at the Iowa Environmental Council, said a data center in Altoona, Iowa, consumes about one-fifth of the water the city is using.

About half of Iowa was experiencing severe or extreme drought conditions in March 2024, and the state’s groundwater levels are declining. So the availability of water—not to mention the quality of water—is already a significant issue

there.

Individual households in the U.S. use about 80 gallons of water per person per day. Water-saving habits, appliances and fixtures, such as washing machines, shower heads and faucets, could reduce that number substantially.

We have made progress in using water more efficiently, through greater awareness about how much water we use in the home or for lawns and landscaping. That’s a sliver of good news. While the population continues to grow, per capita water use has

remained fairly flat in many places in the U.S. and across the globe.

Data centers like this one in Silicon Valley, California are among the nation’s top 10 consumers of water.

Data centers like this one in Silicon Valley, California are among the nation’s top 10 consumers of water.Wasted water

Our water infrastructure is old and leaky, which means we waste a vast volume of water. At utility scale, loss of water due to broken or leaking pipes is a huge and costly problem. A utility system loses revenue along with the lost water.

Households in the U.S. lose a trillion gallons of water per year due to leaks and easily fixable problems, says EPA. Ten percent of households have leaks of 90 gallons per day. Typically, the water is lost through minor problems—dripping faucets,

leaky valves and worn flappers that regulate water in toilets.

Recent action by Congress, like the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law, aims to address waste by helping water managers conserve water and use it more efficiently. See box below, “How to Reduce Your Use” for tips about saving water at home.

Climate

The climate crisis contributes to the scarcity of fresh water in several ways. Warmer temperatures mean more evaporation and greater amounts of moisture in the atmosphere. That translates into extreme weather patterns that produce drought in some places

and flooding in others: dry places are even drier, wet places are wetter.

Flooding means more erosion and nutrients washing off agricultural fields and into waterbodies that serve as sources for drinking water. Nutrients like phosphorus and nitrogen flowing off farmlands can pollute water.

They also foster harmful blooms of “blue-green” algae in ponds and lakes. These blooms produce a toxin, microcystin, that poses dangers to people and pets. The departments of natural resources in several states published warnings last summer

about the poisoning risk to dogs that microcystin poses. See box, “Costs of nutrient pollution that causes algal blooms.”

Warmer temperatures globally also melt ice that raises sea levels. As seawater moves inland, it floods freshwater aquifers, making them useless as sources of drinking water. Along Delaware’s coast, flooding seawater in tidal streams has killed crops

as the salt water pushes farther inland.

The Izaak Walton League’s water monitoring programs like Nitrate Watch and Salt Watch allow volunteers to use free test strips to monitor local

waterways. The volunteers can upload the test results to a public repository for water quality information called the Clean Water Hub which can display

results from more than 56,000 water samples nationwide. Volunteers are also encouraged to report pollution to local officials.

Contamination costs

Water pollution is one of the problems that spurred conservationists to create the Izaak Walton League in 1922. While industrial wastes and sewage dumped directly into rivers and streams was blatant and obvious in the 1920s, the pollutants today—whether

microplastics, nitrate or PFAS—are less visible but equally harmful.

Nitrate. In many places in the U.S., and particularly the Midwest, drinking water sources contain nitrate, which is linked to some cancers and other dangers to people. It forms in the water when nitrogen washes off agricultural lands,

or when sewage systems leak into waterways. The limit set by the federal Safe Drinking Water Act is 10 milliliters per liter (or 10 parts per million) so water utilities must keep water below that level to be considered safe for human consumption.

But recent studies have shown that prolonged exposure at levels below 10 mL per liter increases the risk of several forms of cancer.

In Nebraska, small towns had to make big investments to remove nitrate from their drinking water.

At Des Moines Water Works in Iowa, removing nitrate from drinking water drawn from the Des Moines or Raccoon River costs up to $10,000 per day. A wet spring in 2022 washed a lot of nitrogen into local waterways, which required the utility to use its special

treatment system to remove nitrate and keep water within the EPA limits. A recent spill that dumped concentrated nitrogen fertilizer into a ditch and then into rivers in Iowa and Missouri compounded the expected annual springtime “flush”

of nitrogen washing off agricultural fields into streams and lakes.

For ratepayers who pay the higher water bills and for consumers who drink the water, it’s obviously cheaper and safer to keep carcinogens and other pollutants out of the water in the first place. A host of conservation practices help. Planting cover

crops and reducing tilling so less soil erodes helps keep chemical nitrogen on the field instead of washing into streams and groundwater that supply our drinking water.

In January 2021, the Union of Concerned Scientists released a study predicting that “Iowans will be on the hook for up to $333 million over the next five years to remove nitrates polluting the state’s drinking water supplies and threatening

public health.”

In 2020, the University of Nebraska-Lincoln (UNL) reported that a group of towns—Creighton, Brunswick, Orchard, Osmond and Plainview, with a combined population of fewer than 4,000 residents—were forced to pay nearly $9 million to ensure drinking

water does not exceed the limit for nitrate. That cost works out to more than $2,200 per person in those towns.

The UNL report cited five other examples in Nebraska where small towns had to make big investments to remove nitrate from their drinking water. “When a public water supply well gets contaminated with nitrates above safe levels, the state requires

the community to come up with a solution, such as purchasing new land where they can drill a new well, installing a treatment system or laying pipe to connect to another community’s water system.”

The pollution culprit in Nebraska was excess nitrogen washing off irrigated corn fields. Yet, efforts to renew and improve the popular Farm Bill incentives to reduce nitrogen use—without reduced crop yields—are floundering in Congress.

“As nitrate pollution increases, more and more communities throughout the U.S. will have to invest heavily in building treatment plants to remove nitrates from source waters,” concluded a 2018 study by the Northeast-Midwest Institute. “[M]any

smaller communities are simply incapable of financing the necessary treatment plants without additional support…. By weakening regulations that protect source waters from pollution, Congress and the Executive Branch risk compounding the growing

costs associated with providing clean drinking water.”

Salt. Excess salt applied to roads, sidewalks and parking lots is toxic to aquatic life in high concentrations and can add unhealthy levels of salt to drinking water. Salt is also corrosive to infrastructure and cars, which is expensive

for taxpayers and car owners.

Worse, untreated water with high levels of salt can leach lead from water pipes into residential drinking water. There is no safe exposure level for lead, which can cause neural damage to children. And there are roughly one million miles of lead water

pipes in the U.S. The Biden Administration has announced plans to replace those pipes in the years ahead, but in the meantime, millions of consumers face potential harm from tap water.

PFAS. Another type of chemical making its way into U.S. waterways, fish and drinking water is per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances, or PFAS. Sometimes called “forever chemicals” because they persist and don’t occur naturally,

these compounds are linked to a variety of health problems including cancer, decreased fertility and developmental delays in children.

For ratepayers and consumers, it’s obviously cheaper and safer to keep carcinogens and other pollutants out of the water in the first place.

Scientists from the University of Notre Dame examined more than 100 sportfish from Lake Michigan and found PFAS in all of them, reports Irene Miles for Illinois-Indiana Sea Grant. The PFAS levels “were lower there than in most Great Lakes,”

she wrote. But the researchers reported widespread presence of a very toxic PFAS called PFOS (perfluorooctane sulfonate), particularly in trout and salmon. Production of PFOS ended more than two decades ago, but the compound continues to contaminate

fish today.

The Minnesota Department of Health issued a warning in March 2024 that fish in the Upper Mississippi River from St. Paul to Wabasha should not be eaten because of a high concentration of PFAS found in fish from those waters.

In April, the Biden Administration issued a rule it described as the first-ever national, enforceable drinking water standard for PFAS. “Exposure to PFAS has been linked to deadly cancers, impacts to the liver and heart, and immune and developmental

damage to infants and children,” according to EPA’s statement. The agency also announced funding through the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law to help states “implement PFAS testing and treatment at public water systems and to help owners

of private wells address PFAS contamination.”

EPA estimates that between about 6 and 10 percent of the 66,000 public drinking water systems subject to the rule may need to reduce PFAS to meet the new standards. All public water systems have three years to complete their initial monitoring. They must

inform the public of the level of PFAS measured in their drinking water.

For two common chemicals, PFOS and PFOA (perfluorooctanoic acid), EPA set a Maximum Contaminant Level Goal (a non-enforceable health-based goal) at zero. With that, the agency underscores that “there is no level of exposure to these contaminants

without risk of health impacts, including certain cancers.” EPA also set enforceable Maximum Contaminant Levels at 4.0 parts per trillion for PFOA and PFOS, to reduce exposure in drinking water to the lowest levels that are feasible for implementation.

The American Water Works Association says the cost of removing forever chemicals like PFOS and PFOA will cost billions of dollars per year. This plant treats water in northern Virginia.

The American Water Works Association says the cost of removing forever chemicals like PFOS and PFOA will cost billions of dollars per year. This plant treats water in northern Virginia.Conservation

One enormous source of available fresh water is the water that we can stop wasting. Conservation comes in many dimensions—some require advanced technology and others simply require common sense.

Household strategies can combat the loss of about a trillion gallons of water per year due to leaks, says EPA. One household can leak as much as 10,000 gallons per year, and 10 percent of households have leaks of 90 gallons per day. Typically,

the water is lost through problems that are easy to fix, like dripping faucets.

To address water scarcity, the International Code Council convened a meeting of water experts in Washington in March 2024 to examine conservation solutions that focus on building standards and codes for homes.

In partnership with the University of Miami, the Code Council issued a report, “Water Conservation and Codes: Leveraging Global Water-Efficient Building Standards to Avert Shortfalls,” which examines the critical need for the rapid adoption

of the updated water conservation standards contained in the 2024 International Water Conservation Code Provisions (IWCCP).

The Code Council believes that in addition to utility-scale solutions, individual buildings, including homes, can have an equally powerful effect on conservation.

The report estimated potential water savings for dwellings in Phoenix, Las Vegas, Houston and Des Moines, and established baseline numbers for average use of potable water (for drinking, bathing, etc.) and non-potable use (e.g., toilet flushing), and

it estimated water savings that could be derived from four strategies:

- Adoption of more efficient plumbing fixtures

- Rainwater harvesting, treatment, storage and reuse

- Gray water treatment, storage and reuse and

- HVAC condensate capture, treatment, storage and reuse.

The study projected the water savings if existing 2021 IWCCP standards were applied to lavatory faucets, shower heads, sink faucets, toilets, clothes washers and dishwashers.

For the average single-family house in Des Moines, for example, applying the 2021 IWCCP standards would reduce annual use of water from 60,907 gallons to 47,925 gallons.

See box, “Reduce Your Use,” for tips about saving water at home.

The report also proposes installation of systems in single-family homes and multifamily dwellings to harvest gray water (from bath, shower, laundry, lavatory and HVAC equipment). That water could be used for flushing toilets, which would reduce the use

of potable water from municipal systems for that function. The report found the potential gray water harvesting in Des Moines from “on-site non-potable water reuse systems would reduce the need for municipal water for non-potable uses by an

average of 72 percent.”

For utility-scale conservation there’s an immense need to reduce wasted water. The nation’s water infrastructure is old and leaky, and loss of water due to broken or leaking pipes is a huge and costly problem.

Recent actions by Congress, like the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law, aim to address waste by helping water managers conserve water and use it more efficiently. Bank of America Research argues that every dollar spent on solutions to the water crisis yields

seven dollars in return, through cost savings, health and other benefits. Fixing the problem would require an investment of about one percent of gross domestic product, they assert.

Most analysts agree that existing technologies, practices and policies could go far to solve the water scarcity crisis. That means smarter meters to help detect leaks and problems. Smarter irrigation on farms. Smarter home fixtures and practices. Smarter

investments and policy for the nation’s water infrastructure.

How To Reduce Your Use

- By preventing leaks in pipes and fixtures, the average family can save about 180 gallons of water per week, or 9,400 gallons per year, estimates EPA. That’s equivalent to the amount needed to wash more than 300 loads of laundry.

- Running the dishwasher only when it’s full can eliminate one load of dishes per week and save the average family nearly 320 gallons of water annually.

- Turning off the tap while brushing your teeth can save eight gallons of water per day, assuming you brush your teeth twice daily.

- Less water for irrigation. Outdoor water use accounts for 30 percent of total household water use and as much as 60 percent of total household water use in arid regions.

Source: EPA

Costs of Nutrient Pollution That Causes Algal Blooms

Loading waterbodies with large amounts of nutrients, like nitrogen and phosphorus, can lead to excessive plant and algal growth, resulting in a range of adverse economic effects as well as dangers to health. EPA lists those economic costs:

- Tourism and recreation. Reduced restaurant sales, lakeside business closures and decreased tourism-associated spending. For example, a persistent algal bloom in one Ohio lake caused $37 million to $47 million in lost local tourism

revenue over two years.

- Commercial fishing. Harms to commercial fisheries include reduced harvests, fishery closures and increased processing costs associated with elevated shellfish poisoning risks.

- Property values. Elevated nutrient levels, low dissolved oxygen levels and decreased water clarity can depress the property values of waterfront and nearby homes.

- Human health. Algal blooms can cause a variety of adverse health effects through direct contact with skin, drinking contaminated water or eating contaminated shellfish.

- Drinking water treatment costs. Excess nutrients in source water for drinking water treatment plants can increase costs to treat foul taste and odor as well as health risks.

- Restoration. There are substantial costs for restoring impaired waterbodies such as developing total maximum daily loads, watershed improvement plans and nutrient trading and offset programs.

[EPA Report, “A Compilation of Cost Data Associated with the Impacts and Control of Nutrient Pollution," May 2015]

Top photo: A glass of water with the Izaak Walton League's logo on it. Credit: Michael Reinemer.