My father, Joe Penfold, had a knack for finding common sense and common ground on complicated issues.

Looking back, I realize he actually had several traits that served him well in his role as Western representative, starting in 1949, and later as national conservation director for the Izaak Walton League of America.

Even as a child, I saw the consensus-builder in my father. My brother John and I argued constantly. Pop would listen to each of our complaints. Then, with a simple sentence, he would find a way to solve the problem, whatever it was.

As I learned, his ability to hear all sides of an issue, understand points of agreement and disagreement and craft solutions was a quality that helped him accomplish many policy achievements for outdoor

recreation and conservation.

Bill Voigt also noticed. He was the executive director at the League who hired Dad in 1949. In his history of the League, Born with Fists Doubled, Voigt wrote, “Joe was not one to speak without thoroughly exploring both pros and cons of an issue. This was an innate trait; I doubt if anyone who knew him at any stage of his adult life could cite any instance when he made a hasty, ill-conceived statement in a serious discussion.”

A hallmark of his work was marshalling the power of data, facts and dollar figures when appealing to the public for support.

Over time, I also recognized that my father was good at building trusting relationships with all sorts of people. Many of them were other conservation leaders. They included people like Arthur Carhart, Olaus and Mardy Murie and Howard Zahniser – all leaders in the wilderness movement – as well as iconic Ike and Boundary Waters defender Sigurd Olson, biologist John Craighead and legions of League members across the U.S.

He also established excellent working relationships with lawmakers, such as Representatives John Saylor and Wayne Aspinall, and Senator Frank Church, among others. Their support and their trust in Dad contributed to many conservation achievements.

Fighting a Land Grab

Dad’s first job for the League, based in Denver, put him in the middle of conflicts among Western land stakeholders. Voigt initially had some reservations about whether Pop was equal to the challenge. “My concern was whether this introspective fellow of medium height, slender, reserved, usually soft voice, could handle himself in the rough and tumble land grab atmosphere…and in the interminable brushfires of one kind or another that persisted in breaking out in the West. The worry was needless.”

One of his first duties was fighting the effort by Western livestock grazers to take over public lands for their own use. During the 1940s, cattle ranchers and their allies in Congress pushed to privatize grazing areas on lands managed by federal agencies. The idea was to sell the land to cattle ranchers for as little as nine cents per acre. The “owners” of these federal lands are the American people, and the Izaak Walton League wanted to keep it that way.

League chapters in Colorado and Wyoming were outraged by what they called an attempted “land grab.” Members in the West opposed this transfer of public land to private hands but didn’t feel a lot of support from other regions of the country. So Voigt, Carhart, Dad and other Ikes began working with Bernard DeVoto, a passionate writer for Harper’s Magazine, who took up the cause and shared the land-grab story in a long series of angry articles that reached a large, national audience.

Dad also employed yet another hallmark of his work – a keen interest (Bill Voigt called it an obsession) with marshalling the power of data, facts and dollar figures when appealing to the public for support.

An opinion piece in Denver’s Rocky Mountain News asked, why not sell the public land to ranchers? Dad wrote a response letter, published by the paper, in which he answered that question with one of his own. “Should national forest lands in Colorado be sold to the 1,300 livestock people who use them, or [to] the 1,253,000 campers and picnickers, 246,000 winter sports enthusiasts, or to the hunters and fishermen, about 450,000 who spent 1,200,050 days last year using the national forests in the state?”

In the end, Carhart, Dad and the League won that battle, and the public lands were saved for the next decade or so. This land grab, which did not succeed, was just one assault against the nation’s public lands. There would be many more.

On a boat trip down the Green River in Echo Canyon, Penfold helped two members of Congress appreciate the value of conserving this striking landscape.

On a boat trip down the Green River in Echo Canyon, Penfold helped two members of Congress appreciate the value of conserving this striking landscape.

A Victory Echoes across the Canyons

What emerged next was the effort to keep a dam out of Dinosaur National Monument, a vast area of land spanning from western Colorado into Utah. That land has been set aside as a monument to preserve stunning landscapes.

To manage water resources for western communities, the Bureau of Reclamation (part of the U.S. Department of the Interior) was determined to build a dam on the Green River in a high-walled canyon at Echo Park, which would have flooded the surrounding area turning it into a deep reservoir.

The ensuing fight was about preserving a wild place of great beauty. But more broadly it was about how decisions would be made about public lands and how the conservation community would respond to the threats of many other proposed dams on National Park Service lands.

While some conservation groups made the case for preserving wilderness in Dinosaur National Monument, Arthur Carhart and my father argued for the economic and recreation benefits of preventing the dam. They aimed to line up support from business interests – as well as outdoorsmen and women – focusing on the value of tourism and revenue from recreation.

This is Dinosaur – Echo Park Country and Its Magic Rivers is a collection of essays edited by the writer Wallace Stegner that helped to bring the story of this fight to a national audience. Olaus Murie and Dad together wrote one chapter in the book.

The Echo Canyon fight was about how decisions would be made about public lands and how the conservation community would respond to other threats.

A history book describing this era, A Symbol of Wilderness: Echo Park and the American Conservation Movement by Mark W.T. Harvey, notes the unique role of Joe Penfold and the League.

Harvey wrote, “By 1953, the threat to Echo Park had become a major item on the agenda of many conservation organizations, some of them substantially more powerful in the political arena than the tiny Sierra Club.… [Conservationists] relied heavily on the strength of larger organizations like the Izaak Walton League and the Audubon Society. The weight of conservation sentiment came from sportsmen and birdwatchers, not from national park or wilderness lovers, and that fundamental fact had great bearing on the success of the campaign in Congress.”

“As the campaign continued to coalesce, the Izaak Walton League proved to be especially important. Under the direction of William Voigt, Jr. and Joe Penfold, the League anchored the Echo Park campaign in traditional conservation goals, namely, by looking out for the best ways to ensure good fishing.”

One episode in the fight to save Dinosaur was a boat trip on the Yampa and Green Rivers, which flow through the monument. Dad arranged the trip and invited Pennsylvania Congressman John Saylor, a passionate conservationist, and Wayne Aspinall, a powerful and cranky member of the House Interior Committee whose Colorado district included parts of the monument. Both agreed to go along.

Voigt describes this boat trip in his book. “Lasting friendships began as the party drifted down quiet reaches between spectacular canyon walls, and in conversation around the campfire. Three men – Aspinall, Saylor and Penfold – took each other’s measure in Dinosaur, and liked what they found. Aspinall was an astute politician who knew his continuation in office depended on what he produced for the West, but if approached in a spirit of reason he could respond to sound arguments well presented….

“The value of the trip with regard to Dinosaur’s future must not be underestimated. Conservation achievements in later years made it evident that Penfold’s views received close attention from both congressmen. The boat trip laid the foundation for later communication that brought results to many an area other than Dinosaur.”

In the final congressional authorization in 1956, Aspinall got much of what he wanted for water management, but the dam was kept out of Dinosaur – and other national parks and monuments. Aspinall and Saylor, along with many other groups and individuals, were essential to saving Dinosaur National Monument.

Many historians have chronicled the achievements of the League. A book by William Philpott, Vacationland: Tourism and Environment in the Colorado High Country, describes the status of the League in those days. “Nationally, the Izaak Walton League in the 1940s had more members and more pull with policymakers than any other outdoor group, and in Colorado its brand of conservation played especially well.”

An Outsized Legacy for the Outdoor Commission

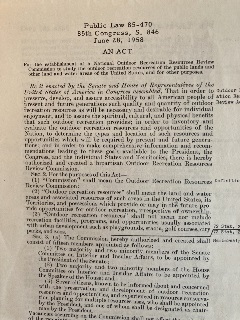

Public Law 85-470 establishing the ORRRC. (Click for larger version.)Before leaving Colorado for League headquarters in Washington, DC, Pop started proposing that a national assessment be made of outdoor recreation in the United States. His experience with Dinosaur Monument and many conversations led him to believe that the nation needed a thorough and formal review.

Public Law 85-470 establishing the ORRRC. (Click for larger version.)Before leaving Colorado for League headquarters in Washington, DC, Pop started proposing that a national assessment be made of outdoor recreation in the United States. His experience with Dinosaur Monument and many conversations led him to believe that the nation needed a thorough and formal review.

This would ultimately come to fruition in the Outdoor Recreation Resources Review Commission (ORRRC), which spun off many ideas and inspirations that would strengthen conservation for decades and decades after.

My father and League colleague Frank Gregg (who later served as executive director) drafted and lobbied for a bill to create the commission, which Congress approved. It was established in June 1958, and Dad served on the commission.

The goal of the commission was to answer three questions:

- What are the recreation wants and needs now and what will they be in the years 1976 and 2000?

- What are the recreation resources of the nation available to meet those needs?

- What policies and programs should be recommended to ensure that the needs of present and future are adequately and efficiently met?

Geographer Brent A. Olson wrote, “The initial findings and recommendations of the ORRRC were released in 1962, and accompanied by 27 supplementary reports… The reports provided Penfold and other environmentalists the ‘voluminous figures’ which they could use in their debates with extractive interests.

“The findings and policy recommendations of the [Commission]… have had a lasting impact on conservation policy and recreation planning on the nation’s public lands. These recommendations removed significant obstacles to the passage of the Wilderness Act, the National Wild and Scenic Rivers Act, and led directly to the establishment of the Bureau of Outdoor Recreation.”

The Land and Water Conservation Fund was perhaps the most significant and consequential outcome of the Outdoor Recreation Resources Review Commission.

The Land and Water Conservation Fund was perhaps the most significant and consequential outcome of the ORRRC. Established by Congress in 1964, the Fund has invested in national and local parks and rec centers in nearly every county in the United States – rural, suburban and urban. Federal agencies have used the funds to acquire important areas that provide access to public lands and protect wildlife habitat. (See cover story, Outdoor America, 2021 Issue 1).

I can include a personal experience with the Fund. During my tenure as a U.S. Forest Service Supervisor of the Jefferson National Forest in Virginia, we were able to acquire thousands of acres of scenic land for the Mount Rogers National Recreation Area, dozens of miles of the Appalachian Trail and a large tract of land that was eventually added to the Eastern Wilderness system. Since retiring, I have successfully advocated for the acquisition of private property in the Pryor Mountains, Four Dancers Natural Area and land along the Yellowstone River in Montana. These acquisitions would have been impossible without the Land and Water Conservation Fund.

Jack Lorenz, who served as executive director of the League from 1974 to 1992, wrote an appreciation for Dad for the Outdoor Writers Association of America called “Joe Penfold, No Ordinary Joe.” In that piece, he says the late Representative Morris Udall once told him “Joe Penfold was the creative genius and driving force behind the most important and far-reaching conservation legislation in American history.”

I admit I’m a little biased – but I have to agree.

Forging a Path to Wilderness

The preservation of wilderness in the United States is the result of decades of work by numerous people. The wilderness system owes much to the leadership of Aldo Leopold and Arthur Carhart, both of whom worked for the U.S. Forest Service in the early days.

The Forest Service, over time, bought into that idea, and federal land agencies created wilderness areas and primitive areas by administrative action. But by the 1940s, ‘50s and ‘60s, conservationists began to understand that the wilderness areas need to be protected by federal law. The problem was that the Forest Service, with a stroke of the pen, could undo the wilderness status of these places.

The Outdoor Recreation Resource Review Commission laid out the foundation for managing public land for recreation and as wilderness as part of the national system. The fight to get the Wilderness Act passed began in the mid-1950s and lasted for almost nine years. There were dozens of drafts and dozens of hearings in Congress. But in the end, passage of the bill hinged on resolving differences between Representatives John Saylor and Wayne Aspinall, who could not agree on some of the provisions.

Here is where Joe Penfold comes in. Remember he had good working relationships with both Saylor and Aspinall. Pop sat down with Aspinall, knowing the problem that Saylor had with the bill, and he drafted alternative language that he knew Saylor would accept. With that problem solved, the path to passing the Wilderness Act into law would be easy. Today, the law protects 111 million acres of vital wildlands in pockets large and small from Alaska’s Denali National Park to Florida’s Everglades.

Pop told me one time, “there is no limit to the amount that one can get accomplished if one does not care who gets the credit.” How true. On the list of important people and organizations who saved American wilderness you rarely see mentions of Joe Penfold or the Izaak Walton League.

Interior Secretary Stewart Udall presents Joe Penfold with the Conservation Service Award May 25, 1962, citing his leadership on the outdoor commission.

Interior Secretary Stewart Udall presents Joe Penfold with the Conservation Service Award May 25, 1962, citing his leadership on the outdoor commission.

An Honest Broker

It’s humbling to recall what individuals working with the Izaak Walton League have accomplished over the past century.

It’s fair to say that there were simply fewer movers and shakers in the outdoor recreation / environmental movement in those days. In that era, people tended to get along and work together across different organizations. My dad was certainly not angry at people who had a different point of view or value system. And in the ‘50s, ‘60s and ‘70s, there was much more collaboration between political parties than we see now.

One thing became clear after my father passed in 1973. He was considered an honest broker. People trusted what he had to say. I would occasionally meet people who knew Dad and would tell me things I did not know about him. Their tone was respectful. Sometimes it almost felt like love.

Once, when I met one of Pop’s colleagues, he looked at my hands and said, “My God, your hands look like your father’s.” There was a tear in his eye.

Top photo: One of Penfold's first assignments at the League was to keep federal public lands in the West from being sold off to cattle ranchers. Credit: Pixabay.