The 1950s and 1960s were filled with significant shifts in American life. This period started with the Cold War and ended with Woodstock. In between were advancements in civil rights and gender equality. America lost youth in two wars overseas. We lost promising leaders to assassinations and activists to local clashes. Elvis Presley appeared on The Ed Sullivan Show, the Beatles invaded America, and Neil Armstrong became the first man to walk on the moon. Poodle skirts and bobby socks gave way to long hair and peace signs.

As American culture shifted, so did the threats to America’s natural resources. It’s difficult to summarize such an era of change. But we can highlight a few significant issues on which the League led the nation.

Finding Outlets for Outdoor Recreation

As the nation’s prosperity increased after World War II, so did disposable income. Americans moved to the suburbs and bought cars and televisions. They took family vacations that often included trips to state and national parks. This put more pressure than ever on the nation’s outdoor resources, and different uses of these resources began to conflict with one another. Could America’s system of public lands and waters keep up with the demand? No one knew. The federal government did not have a good picture of recreational resources, the demands on these resources, or a national vision for the future of outdoor recreation.

The Izaak Walton League, under the leadership of IWLA conservation director Joe Penfold, stepped in to address this shortfall. The League crafted legislation to establish a national Outdoor Recreation Resources Review Commission (ORRRC) to evaluate the nation’s recreation resources and project future trends. The proposed commission would include four members each from the U.S. House of Representatives and U.S. Senate and seven citizens to be appointed by the president.

In June 1958, President Eisenhower signed the Outdoor Recreation Resources Review Act into law. Joe Penfold was one of the seven ORRRC members appointed by the president. Laurance Rockefeller (who helped secure the Jackson Hole National Monument in the 1940s) headed the commission. The commission’s task was to make a three-year study of the nation’s outdoor recreation resources and project the nation’s need for these resources in 1976 and 2000.

The commission released its “Outdoor Recreation for America” report in January 1962. In it, the commission highlighted the need for a national outdoor recreation policy and spelled out specific roles for federal, state, and local governments as well as private organizations and individuals. The report also recommended creating a Bureau of Outdoor Recreation in the Department of the Interior and a federal grant program to help states develop areas for outdoor recreation.

To bolster local outdoor recreation opportunities, the League launched an Outdoor Recreation for America Program. “Recreation areas of all types should be close at hand in all population areas so recreation can be enjoyed frequently by any member of the family,” said IWLA national president Burt Brickner. Chapters across the country answered the call to action. For example, a chapter in Oregon worked with a local manufacturing company and the U.S. Forest Service to build a lake-side campground not far from downtown Portland. A Wyoming chapter near the North Platte River built a public tent and trailer camp on its property because there were no overnight facilities for people touring the area. Other chapters started water quality monitoring programs to support anti-pollution efforts and educate the public.

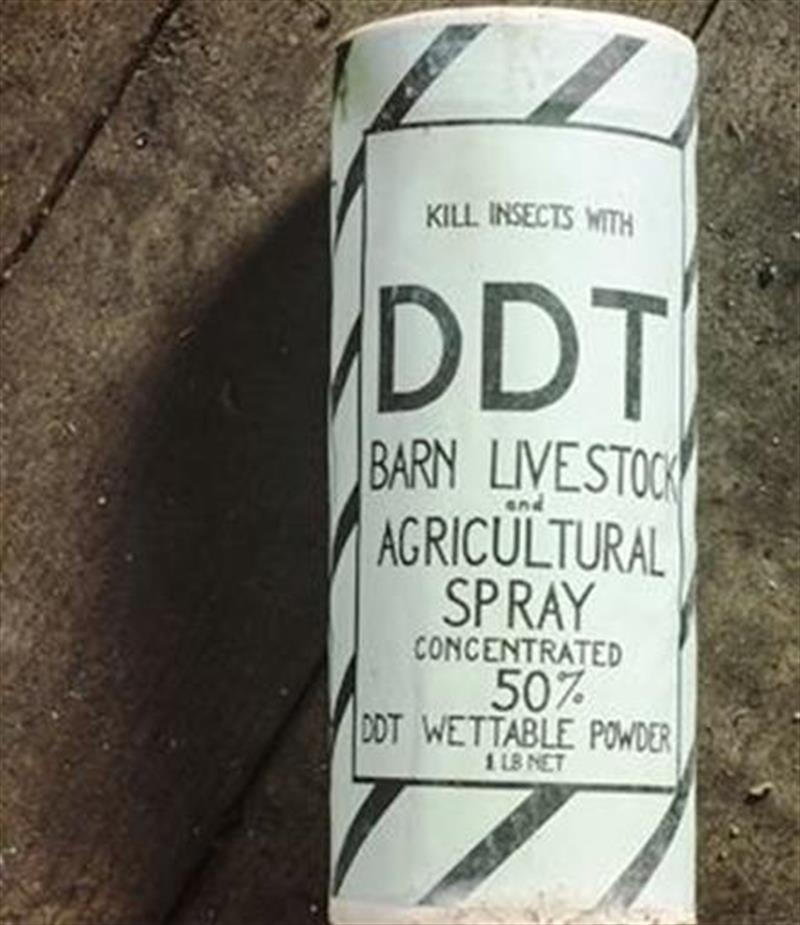

Driving Opposition to DDT

DDT (dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane) was created as a chemistry experiment with little thought to its use outside the lab. In fact, a Swiss chemist stumbled on the chemical’s insect-killing prowess after he took a sample home and tried it on his house flies. By the early 1940s, the United States was producing vast quantities of DDT and shipping it around the world to prevent typhus and malaria among military personnel. After World War II, the use of DDT shifted to the war on insects in agriculture and forestry.

Part of what made DDT so effective was its “persistence” — it could continue to kill months after it was sprayed. However, there was growing evidence that DDT was killing more than just insects. Birds died from eating contaminated worms. Populations of osprey, bald eagles, pelicans, and peregrine falcons plummeted because DDT damaged the birds’ ability to retain calcium, resulting in thinner eggshells that broke well before baby birds were ready to hatch.

Fish were affected too. Some species declined because the insects on which they fed were exterminated by DDT-laden runoff. Other fish were killed outright. For example, DDT sprayed over 2,000 acres of Florida tidal marsh wiped out more than one million fish but had zero impact on its intended target, the sand fly population.

The Izaak Walton League expressed concern about DDT as early as 1952, when Outdoor America published “Are Chemicals Killing Our Fish and Wildlife?” The article, written by biologists from the U.S. Public Health Service, addressed fish kills and loss of wildlife due to pesticides. However, the authors attributed these deaths to over-use or misuse of chemicals, declaring that some chemicals (and some loss of wildlife) were necessary to ensure America’s food supply.

League leaders pushed back against the notion of acceptable losses of fish and wildlife and raised concerns about human health as well. In 1954, IWLA national secretary Robert O’Hair urged League convention delegates to develop a “well-defined and definite policy attitude” on DDT. Delegates passed a resolution calling on the Public Health Service, Food and Drug Administration, and U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) to broaden their investigations into the toxic effects of new insecticides and other chemicals.

When action lagged at the federal level, the League looked to the states to make progress. In 1961, the League’s national Insecticides and Pesticides Committee developed a model state law for regulating pesticides, which the League circulated to chapters and divisions across the country. This was the basis of state-level action in many areas.

In 1962, former U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service biologist Rachel Carson published Silent Spring, which detailed the dangers of indiscriminate pesticide use, especially long-acting chemicals such as DDT. The book sparked concern from small towns to the White House.

Public opinion was further inflamed by a massive fish kill on the Mississippi River. The Public Health Service traced the kill to a small amount of endrin (a pesticide promoted as less toxic than DDT) that leaked from a chemical plant in Memphis. IWLA national president Burt Brickner sent a letter to the Secretary of Health, Education, and Welfare demanding a complete ban on such pesticides, emphasizing that “the time for drastic and effective action is now at hand.” The League presented its case at a Department of Agriculture hearing in April 1964, stating that DDT and similar pesticides “constitute a basic threat to our total environment and to national health itself, a threat which can no longer be tolerated.” When USDA failed to adequately respond, the League filed a lawsuit in the U.S. Court of Appeals.

When Congress established the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) in 1970, the agency assumed responsibility for federal regulation of pesticides. By June 1972, EPA had cancelled all crop and non-health uses of DDT in the United States. However, the United States continued to export DDT to other countries for many years.

Saving Land in the Soil Bank

By the 1950s, the nation’s farmlands, prairies, and wetlands had experienced decades of extremes. During World War I, demand for farm products rose to feed America’s allies — and millions of acres went under the plow. In the 1930s, drought and poor farming practices combined to turn America’s heartland into a Dust Bowl. World War II caused another surge in demand. After the war, demand dropped significantly but production levels remained the same. As surpluses rose, prices plummeted. America’s farmers were again in danger of losing their livelihoods, this time not to drought but to surplus.

To aid America’s farmers, the federal government bought the crops that farmers could not sell at a “fair” market price. This arrangement provided economic relief to farmers but did nothing to halt over-production and its toll on the nation’s land and water resources. At the League’s 1954 national convention, delegates approved a resolution making farm subsidy payments contingent on soil conservation practices. Following this resolution, the League’s Land Use Committee developed “A Land Restoration-Price Support Farm Program for the United States” (later shortened to the “Walton Soil Plan”) and presented it in the December 1954 issue of Outdoor America. The Land Use Committee proposed that the U.S. Department of Agriculture “lease from the owners, and remove from all agricultural production, a sufficient acreage of cultivated land to bring production in line with current demand…. A lease provision would be that the land be immediately conditioned and planted in accordance with specifications calculated to assure the highest practical degree of fertility, stabilization, and restoration.”

League leaders shared the Walton Soil Plan with other stakeholder groups. In fact, the League invited representatives from the American Farm Bureau Federation, National Farmers Union, and National Association of Soil Conservation Districts to the League’s 1955 national convention to talk about the proposal; each organization voiced support for sections of the plan.

IWLA Land Use Committee chairman George Hockenyos also discussed the proposal with top officials at the National Grange, U.S. Soil Conservation Service, and “several influential members of Congress.” In fact, he reported, “the proposal of the League contained so many thoughtprovoking aspects that a Departmental Committee [was] formed by [Agriculture] Secretary Benson to study and report on it.” Trade and specialty magazines also reprinted the League’s proposal.

It’s not clear what, if any, interaction League leaders had with the White House on this topic. But in 1956, the Senate Agriculture Committee held hearings on a soil bank plan proposed by the Eisenhower administration. League representatives spoke at the hearings to urge that wildlife values be included in the plan.

When signed into law, The Agricultural Act of 1956 included the Soil Bank Act, which authorized a conservation reserve program to improve soil, water, forestry, and wildlife quality. To support wildlife conservation, the League launched “Make the Soil Bank Work.” The League’s national office provided materials to chapters that explained the conservation reserve and forestry, wildlife, and fishery practices in each state. Chapters were asked to use these materials to interest local landowners in the conservation reserve and work with them to establish game and fish populations — even help pay part of the cost of wildlife, forestry, or fishery practices. The Soil Bank ultimately took 29 million acres of farmland out of production.

The Soil Bank Act was repealed in 1965. However, out of this effort grew the Conservation Reserve Program enacted in the Food Security Act of 1985 (better known as the Farm Bill). The Conservation Reserve Program remains a powerful tool today to prevent erosion and soil loss — when it is adequately funded. The Department of Agriculture routinely receives more applications for program enrollment than it has funds to enroll, and congressional funding routinely falls far below what the Farm Bill allows. During annual budget debates, the League works to ensure the strength and effectiveness of this program.

Hunter Safety and Outdoor Ethics

In 1954, 13 hunters were killed and 37 seriously injured in Oregon due to “mishandling of firearms.” The League’s Portland Chapter launched a program called Red Hat Day — named after the safety apparel worn by some hunters — to encourage safe hunting. This program quickly grew into a state-wide initiative sponsored by the governor and 25 other organizations. Hunters were urged to wear a red hat to show their commitment to living by the Red Hat rules: Respect the property and rights of others, obey game laws, and be careful with fire and firearms. More than 75,000 pledge cards were distributed in the first year of the Oregon program.

At the League’s 1956 national convention, delegates adopted a resolution recommending the Red Hat Program as a national League initiative. League leaders and staff went to work on the mechanics required to translate the state program into a national effort. The League’s Executive Board designated September 1957 as the first national Red Cap Month. “The principal aim of Red Cap Month will be to call national attention to the hunting code of the Izaak Walton League: To foster safety in the use of firearms, to promote respect for the rights of property owners by hunters, to call attention to the legal and moral laws of conservation, and to prevent range and forest fires,” reported the May-June 1957 issue of Outdoor America. The League later added to that list the need to “help perpetuate hunting as a national sport for ourselves and future generations.”

Red Cap Month was sponsored jointly by the League, the National Sporting Goods Association, and Field & Stream magazine. The program was endorsed by President Eisenhower and numerous governors, mayors, and civic officials. The League provided chapters and divisions with promotional materials, including sample proclamations, window stickers, posters, and pledge cards.

In 1958, the League modified the program to more directly address hunter-landowner relations. The name was changed to Hunt America Time (HAT). In an August 1958 editorial in Outdoor America, IWLA executive director Frank Gregg declared, “America’s tradition as a nation of hunters is in trouble. Maintaining game populations is itself a staggering job in this era of clean farming, pothole drainage, insecticides, and highway and urban expansion. Providing a place to hunt is another, and even tougher, job. Even the most vigorous expansion of publicly owned hunting areas will fall far short of the need. Nationwide, some 80 percent of hunting trips are taken on private lands today — and the proportion will increase. Unmistakably, public hunting depends on private land.”

In addition to working with hunters, the League recommended that chapters reach out to landowners to explain the HAT program, provide them with “Hunting by Permission Only” and “Safety Zone” signs, invite them to a landowner appreciation event, and stay in contact during and after hunting season.

In the first year of the Hunt America Time campaign, 212 League chapters bought promotional HAT materials for local programs. The 54 chapters that reported their program results distributed 15,000 pledge cards and posted more than 13,000 “Hunting by Permission Only” signs. As a result, 35,000 new acres were opened to hunting. By 1960, the League reported that more than 100,000 acres of land had been opened to hunting by permission through the efforts of League chapters. In the ensuing decades, the League’s outdoor ethics focus shifted to all outdoor recreation users.

Reaching Out to America’s Youth

At the 1953 national convention, League leaders announced a new youth program. “Young Outdoor Americans” from every state would attend the IWLA national convention, where an award would be presented to the youth “judged to have made the greatest achievements in the field of conservation in the country.” The League asked each state governor to set up a committee to meet with youth, youth group leaders, and natural resource professionals to discuss state natural resource issues and select young persons to attend the convention. Actor Gary Cooper — best known for his performances in “The Pride of the Yankees” (1942) and “High Noon” (1952) — served as honorary Young Outdoor Americans program leader for the first year.

Youth from all 48 states (Alaska and Hawaii were not states yet) attended the 1954 National Young Outdoor Americans Conservation Planning Conference, held during the League’s national convention. The youth discussed conservation topics and reported their recommendations to IWLA convention delegates.

Subsequent conferences were smaller but continued to bring together youth conservation leaders. In 1958, the youth proposed that the League establish a national conservation organization just for young people. The League investigated the possibility but decided it was more practical instead to “help League chapters and divisions to contribute effectively to the education of youth in sound resource conservation principles.”

The Young Outdoor Americans program ended in 1959, but the League’s engagement with youth did not. Over the next decade, League chapters and divisions continued to work with youth at the local level while national leaders looked to the future.

At the 1969 IWLA national convention, the League again convened a panel of young adults to talk about involving youth in conservation. “It was a classic confrontation — the Young Turks vs. the Old Guard,” reported Outdoor America. “But it again established the academic right of youth to participate in affairs of the world. And youth displayed a strong desire to actively enter the realm of environmental conservation.” The youth stressed that if young people were to be enlisted by the League, it must be as equal partners. Others talked about the need to take conservation efforts to urban areas.

The League convened a Task Force on Young People to advise League staff on youth outreach. “Two things were made obvious by this group,” reported Outdoor America in May 1970: “The Izaak Walton League, in general, is not in touch with young America, and strong measures are needed to put the League in the ‘swing’ of things and ensure its effectiveness — andsurvival — in the immediate future.” The Task Force was renamed Young Americans for Resources and Environment (YARE) and continued to work with the League on youth issues.

League Eliminates Litter Bugs

Many of us have called someone a “litter bug,” but few know that the League’s Portland (Oregon) Chapter popularized the term. Trash along highways and in state and national parks had become an increasing pollution problem after World War II. The Portland Chapter wanted to change public perception about littering. In the early 1950s, the chapter proposed a range of actions to address this problem, including

- Urge the auto industry to design waste-disposal accessories for cars

- Encourage gas stations to stock waste paper bags and provide trash cans at stations labeled “Keep America Beautiful” and “Don’t be a Litter Bug”

- Support increased funding for the U.S. Forest Service, National Park Service, Oregon Parks and Highway Departments, and cities for more trash cans and collection services

- Educate outdoor, civic, and youth organizations and encourage these groups to adopt recreation areas for clean-up

This project quickly gained the support of the League’s Oregon Division and national leaders. At the 1953 IWLA convention, delegates passed a resolution endorsing the Oregon campaign and directing the League’s national office to encourage other League chapters to engage in similar efforts. That year, the Iowa Division supported a statewide campaign against litter bugs and vandalism, and other state divisions — including South Dakota — soon followed suit.

Oregon Division members led other League efforts to fight litter. They teamed up with the state highway department to place trash cans along highways in the northwestern part of the state. The highway department spent more than $100,000 each year to pick up litter along these roads and estimated that it would save a considerable amount of money if the pilot program worked. The division also sponsored a state law making it a misdemeanor to litter within 100 yards of any stream, lake, or reservoir. The League encouraged other chapters and divisions to follow suit.

In 1964, the League’s Anti-Litter Committee sponsored its first national photo contest, asking for “before and after” litter clean-up photos. The following year, the committee sponsored an anti-litter slogan contest. The winning entry of “Reconsider Before You Litter” was submitted by a high school student from Leesburg, Virginia. The committee also sponsored an antilitter pledge contest. By 1968, more than 80,000 students from more than 230 schools had signed the League’s anti-litter pledge.

New Battles for the Boundary Waters

Located in the northern part of Minnesota’s Superior National Forest, the one million acres of the Boundary Waters Canoe Area (BWCA) provides exceptional outdoor recreation opportunities as well as wildlife habitat and clean drinking water. Since the Izaak Walton League’s early days, League members defended the BWCA against numerous threats to its wilderness values — from clear cutting to road development and airplane traffic. But by the early 1960s, new threats were on the horizon. One was the rapid growth in visitors. In 1946, the BWCA had 29,000 visitors; by 1963, that number grew to 230,000. These outdoor enthusiasts brought with them increased use of motor boats, tow services, camps, and other activities that eroded the “primitive” outdoor experience.

At a 1963 meeting of the League’s Minnesota Division, members were vocal about their dissatisfaction with the U.S. Forest Service’s management of the Boundary Waters Canoe Area. They reached out to other citizens and grassroots organizations and created a groundswell of public demand for action.

Logging also cut into enjoyment of the area. When the Boundary Waters Canoe Area became part of the National Wilderness Preservation System in 1964, it gained some protections but remained subject to “special limitations,” including permission to log about two-thirds of the Canoe Area’s one million acres.

In May 1964, U.S. Secretary of Agriculture Orville Freeman appointed a Boundary Waters Canoe Area Review Committee to review the management plan put in place by the Department of Agriculture. Raymond Haik, a leader in the League’s Minnesota Division, was the only person appointed to the review committee from a conservation organization.

The IWLA Board of Directors submitted BWCA management recommendations to the review committee, including the elimination of commercial logging, motorized travel, and the threat of mining; adding “essential portions” to the BWCA by acquiring private in-holdings; and establishing a user permit system to relieve recreation pressure.

In early 1965, following the review committee’s report, Secretary Freeman ordered the U.S. Forest Service to immediately transfer 150,000 acres to the “no cut zone” and an additional 100,000 as soon as lumber company contracts could be renegotiated. Other orders included eliminating mechanized travel, including snowmobiles, on portages and public landings; establishing a system of motorboat zoning; establishing visitor registration; and improving hunting and fishing opportunities. The League supported these and other management changes.

Mineral mining continued to be a threat — not only efforts to mine inside the BWCA but the potential impact of drainage from mines on the outer edges. In December 1969, the Izaak Walton League filed a suit in U.S. District Court to prohibit mine exploration in the Boundary Waters Canoe Area. The suit was filed by Raymond Haik, then the League’s national president, who said, “It is hoped that the suit will bring a precedent-setting decision on federal laws governing wilderness areas [and] set forth the principle that protection of these areas from commercial development supersedes mineral claims still allegedly held by individuals.”

In January 1973, Minnesota Federal District Judge Philip Neville ruled in favor of the League, stating, “A wilderness purpose plain and simple has to be inconsistent with and antagonistic to a purpose to allow any commercial activity such as mining within the Boundary Waters Canoe Area.” Judge Neville issued a permanent injunction against mining activity in the Boundary Waters Canoe Area, even on privately owned land.

However, the Boundary Waters were still open to logging and other motorized incursions due to loopholes in The Wilderness Act of 1964. The League continued to battle for true “wilderness” protection for the area and conceived of the Boundary Waters Canoe Area Wilderness (BWCAW) Act to do it. The Act, signed into law in 1978, terminated logging of virgin forest in the Boundary Waters, banned snowmobiles, established motorboat quotas, and prohibited exploration for and mining of minerals. Today, the BWCAW is the most heavily used wilderness in the country, with approximately 250,000 visitors annually.

A Preview of Change

Many of the League’s accomplishments in the 1950s and 1960s were stepping stones to significant national environmental legislation to come. By the end of the 1960s, the Cuyahoga River had caught fire — not for the first time — and Lake Erie had been declared dead. The spirit of activism that marked civil rights and anti-war efforts in the previous two decades spurred similar efforts to protect the environment. The first Earth Day was held in 1970, and passage of the Clean Water Act followed close on its heels in 1972. The rest of the country was finally catching up with the League’s conservation ethic.

Support our ongoing work